By Alexandria Johnstone, Legal Community Impact Intern & Community Advocate: Resource, Referral, Youth Outreach, Disability & Poverty Law Advocacy

While the Canada Workers Benefit (CWB) has benefited some Canadians since its implementation, some individuals still qualify but cannot claim it due to its harmful effects. Indirect and direct discrimination against marginalized groups can be seen within this federal program, and it is high time for change.

Program Overview

The CWB is a program that provides a refundable tax credit through the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) to help individuals and families that are both actively working and low-income (Canada Revenue Agency, 2023b). As defined by this program, low income has a net income of 33k/year for an individual and 43k/year for families (Canada Revenue Agency, 2023b). One may qualify for two possible CWB payments: the basic amount of $1428 for individuals and $2461 for families and a disability supplement of $737 for individuals and families receiving the same amount (Canada Revenue Agency, 2023b). However, only those approved for the disability tax credit (DTC) during the prior tax season can receive the CWB disability supplement, regardless of if they were receiving provincial disability payments or federal disability payments (Canada Revenue Agency, 2023b). According to the CRA, one is low income for those receiving DTC when one makes less than $37932 as an individual or $48124 as a family (Canada Revenue Agency, 2023b). If both spouses receive the DTC, those with a net family income of less than $53037 will qualify for the basic and supplement payments (Canada Revenue Agency, 2023b). However, only one CWB disability supplement can be received, regardless of both spouses qualifying (Canada Revenue Agency, 2023b).

Due to their similar goals, the CWB replaced the Working Income Tax Benefit (WITB) in 2019. The most noticeable difference between the two programs was that WTIB initially aimed to stimulate provincial economic growth while providing continued working incentives. In contrast, CWB aims to tackle this problem nationally (Canada Revenue Agency, 2020). The WTIB was provided to individuals with an income of over $3000 and below $32244 or under $42197 for families (Kubes, 2022). Although the CRA distributed payments, amounts varied for the WTIB payments as provinces calculated amounts given, with a max payment for an individual seen in BC of $1218 and a low of $665 seen in NU (Boat Harbour Investments, 2023). This program also had a disability supplement, which only those on both the DTC and provincial/territorial disability programs qualified for, which distributed $529 to each qualifying individual, except for in NU which only allocated $332 per person (Boat Harbour Investments, 2023). CWB is more efficient as increased amounts are given to all qualifying Canadians (Canada Revenue Agency, 2020). CWB was seen as an incentive for the working class due to decreased numbers in the workforce and increased living costs since WITB’s creation (Canada Revenue Agency, 2020).

Theory of Change

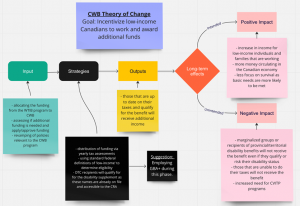

A theory of change assists in the program’s evaluation as it looks to explain how actions produce results that achieve intended impacts of an event, policy, program, or organization (Rogers, 2014). Through inputs (resources used) and outputs (direct or immediate effects on rightsholders), various intended and unintended outcomes, and impacts (positive, negative, primary, and secondary long-term effects) can be achieved (Rogers, 2014). Rightsholders are actors interested in the problem or issue, hold influence in or around it, or are affected via the end policy or program (Varvasovszky & Brugha, 2000). Networks and rightsholders are essential for the government to manage and realize goals, as some rightsholders have resources or capacities outside of what government bodies can offer (Pal et al., 2021). Successful policy implementation entails substantial degrees of private and public cooperation and interaction at every process phase (Pal et al., 2021).

There are two main categories to consider within discussions of rightsholders. The first is primary rightsholders with direct impacts or immediate concerns in the issue or proposed solution (Varvasovszky & Brugha, 2000). For example, in the flowchart, DTC recipients would be considered primary rightsholders as they are highly impacted by the CWB and will experience a direct impact from any changes made to the disability supplement.

The theory of change flowchart visually displays each step of the program’s creation in its attempts towards its goals so that an effective strategy can be created and possible outcomes. Note that the flowchart is not exhaustive, as this program require constant additions, reassessments, and analysis as new data is collected and changes are implemented. However, this analysis aims to identify strengths, weaknesses, and suggestions to create the best strategy to carry out the CWB and subsequent programs.

Additional impacts can also be seen from the chosen structure, implementation, and tools associated with the CWB. The flowchart displays the input into the program as funding and staffing resources. Strategies of the CWB would be the provision of payments and allocation of money. The direct effects of the CWB are payments received by those that are working and low-income in Canada, that are also up to date on their taxes. However, those that are unable to do their taxes or do not have a Community Volunteer Income Tax Program (CVITP) available do not receive the benefit(s), even if they qualify as the CRA has attached this payment to yearly tax assessments.

Impacts

The CWB program is beneficial as it provides additional income to low-income Canadians. However, this program has multiple barriers and adverse long-term effects for certain low-income groups. One negative aspect of the CWB is that if one is attending post-secondary, they do not qualify, even if they are working and low income (Canada Revenue Agency, 2020; Canada Revenue Agency, 2023b; Boat Harbour Investments, 2023), which does not incentivize post-secondary students to work while going to school, but rather encourages the opposite.

Another aspect of the CWB is that it assumes those that qualify for the payments will be able to do or get their taxes done. This is unreasonable as it does not acknowledge that low-income individuals are generally part of marginalized groups and require assistance (Reutter et al., 2009). If completion of taxes is going to continue to be how eligibility is determined, it would be necessary to increase year-round CVITP programming to remain equitable. CVITP is a CRA program that assists low-income individuals and families in filing their taxes at no cost (Beckett, 2022; Government of Canada, 2023). While the CVITP program currently exists, expanding the program would require additional planning, equipment, funding, and travel expenses (Beckett, 2022; Government of Canada, 2023), as well as additional volunteers able to attend remote and rural areas.

The WTIB’s requirement of being a part of a provincial disability program and the DTC created many barriers to access (Canada Revenue Agency, 2020; TurboTax Canada, 2022; Boat Harbour Investments, 2023). Each province holds different criteria for their respective disability programs, hence why disability designations are not transferable between provinces (Government of British Columbia, 2023). While it is no longer required to be a part of both programs (Canada Revenue Agency, 2020; TurboTax Canada, 2022; Boat Harbour Investments, 2023), if one receives DTC, provincial assistance, and CWB, they face their unique set of challenges.

Those on provincial social assistive programs are often penalized for receiving the CWB. While federal disability looks at one’s ability or inability to work (Government of Canada, 2022), the DTC and provincial programs look at the impacts of mental or physical conditions on one’s daily living ability (Canada Revenue Agency, 2023a; Government of British Columbia, 2023); therefore, they can work part-time if they have the capacity. Using BC as an example, one can only make 15k/year, including employment, EI, GST, or other means while receiving assistive payments (Government of British Columbia, 2023). As federal payments such as GST are not exempt from the earnings legislation under the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction (MSDPR), one could be penalized for going over the 15k allotment by receiving such payments (Government of British Columbia, 2023). Furthermore, once one exceeds the 15k allotment, they no longer receive any disability payments for the following year (Government of British Columbia, 2023), further perpetuating cycles of poverty and houselessness. More work must be done to ensure those on various provincial disability programs would not lose their disability designation due to a benefit incentivizing them to work, such as enforcing exemptions of federal government payments.

Suggestion

While the program met the needs of some low-income individuals, additional barriers made it difficult for all those that qualified to receive payments. An improvement that can be made to this program is applying a gender-based analysis (GBA) during the strategy or implementation phase would assist the CRA in avoiding the unintended negative impacts of the CWB program, as illustrated in the flowchart. In employing an intersectionality lens under GBA+, government entities like MSDPR and CRA, remain responsible for equitably filling gaps seen by low-income working Canadians.

Policymakers and analysts must consider why and how policies will affect diverse populations so that the following policies and communications can remain efficient and productive (Hankivsky et al., 2019). Pal et al. (2021) discuss the impacts of problems and proposed policy among various groups in society; the GBA and gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) will assist in discussions of oppression and marginalization of low-income groups, such as seniors and persons with disabilities. In addition, GBA+ focuses explicitly on policy implications for women, men, nonbinary persons, and other intersecting identities which have historically faced inequity (Pal et al., 2021).

Through using the GBA or GBA+, edits to the CWB program can be made to ensure all people that qualify receive payments without penalty, or movements toward a different program can be made. CWB is rooted in neoliberal idealism as it looks to incentivize Canadians to work, not considering other factors that have led to the decline in the workforce. The neoliberal era has typically placed one’s value on their ability to work and economically provide (Simon, 2001). A program such as universal basic income (UBI) would avoid the negative effects seen through the CWB; it would remain low-barrier and accessible to all Canadians as it would be equally distributed to citizens, regardless of disability status or tax completion. This would also lessen the costs associated with CTIVP expansion, funded by the CRA (Beckett, 2022; Government of Canada, 2023), as it would be necessary to improve the CWB program. One may also argue that a UBI may take away productivity, but no data suggests that the motivation to earn money would be reduced, especially within a capitalist society (Simon, 2001).

A UBI model in Canada would be much more efficient in spurring economic growth by allowing for discretionary income, incentivizing productivity, and assisting individuals in accessing universal needs like food and housing (Simon, 2001). However, neoliberalism perpetuates within current Canadian systems and a citizen’s value is linked to their ability work (Simon, 2001). Regardless of a CWB or UBI program being used going forward, all programs should employ GBA+ throughout the process to avoid additional barriers to recipients, starting in the strategy and implementation phases. The federal government should also ensure disability supplements can be received without risk to one’s provincial or territorial disability designation. Through collaboration between provincial bodies (like MSDPR in BC) and the federal government, benefits like the CWB can be optimized to ensure economic growth, while equitably incentivising all Canadians to work.

References

Beckett, B. (2022). Community Volunteer Tax Program: Program overview. Penticton & Area Access Centre.

Boat Harbour Investments. (2023). Line 45300 Canada workers benefit (CWB) refundable tax credit: Formerly working income tax benefit (WITB). Taxtips. https://www.taxtips.ca/filing/canada-workers-benefit.htm.

Canada Revenue Agency. (2023a, Jan. 24). Disability tax credit (DTC). https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue agency/services/tax/individuals/segments/tax-credits-deductions-persons-disabilities/disability-tax-credit/eligible-dtc.html.

Canada Revenue Agency. (2023b, April 7). Canada workers benefit. https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/canada-workers-benefit.html.

Canada Revenue Agency. (2020). Canada workers benefit: Working income tax benefit before. https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/programs/about-canada-revenue-agency-cra/federal-government-budgets/budget-2018-equality-growth-strong-middle-class/canada-workers-benefit.html.

Government of British Columbia. (2023, March 1). MSDPR BCEA policy & procedure manual. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/policies-for-government/bcea-policy-and-procedure-manual.

Government of Canada. (2022). Canada pension plan disability benefits. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/publicpensions/cpp/cpp-disability-benefit/eligibility.html.

Government of Canada. (2023, Feb. 14). Free tax clinics: Through the community volunteer income tax program (CVITP), community organizations host free tax clinics where volunteers file tax returns for people with a modest income and a simple tax situation. https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/individuals/community-volunteer-income-tax-program.html.

Hankivsky, O., Grace, D., Hunting, M., Giesbrecht, M., Fridkin, A., Rudrum, S., Ferlatte, O. & Clark, N. (2019). An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework: Critical reflections on a methodology for advancing equity. In Hankivsky, O. & Jordan-Zachary, J. (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of intersectionality in public policy (133-166). Palgrave.

Kubes, D. (2022). What is the working income tax benefit? Wealthsimple. https://www.wealthsimple.com/en-ca/learn/working-income-tax-benefit.

Pal, L., Auld, G., & Mallett, A. (2021). Beyond policy analysis: Public issue management in turbulent times. Nelson.

Reutter, L., Stewart, M., Veenstra, G., Love, R., Raphael, D., & Makwarimba, E. (2009). “Who do they think we are, anyway?”: Perceptions of and responses to poverty stigma. Qualitative health research, 19(3), 297-311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732308330246.

Rogers, P. (2014). Theory of change (Methodology Brief and Impact Evaluation No. 2). UNICEF Office of Research. https://www.betterevaluation.org/sites/default/files/Theory_of_Change_ENG.pdf.

Simon, H. (2001). UBI and the flat tax. In Widerquist, K., & Wispelaere, J. (Eds.), Basic income: An anthology of contemporary research (240-242). Beacon Press.

TurboTax Canada. (2022, April 1). Tax basics: How taxes work in Canada [Video file]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?list=PL491SLBXGhzhdPw5vM-K E8G0FwhEhZag&v=jRfM94XHLwM&embeds_euri=https%3A%2F%2Fturbotax.intuit.ca%2F&source_ve_path=OTY3MTQ&feature=emb_imp_woyt.

Varvasovszky, Z., & Brugha, R. (2000). A stakeholder analysis. Health policy and planning, 15(3), 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/15.3.338.